We are getting older faster

There has not been a census of population in Lebanon since 1932. This is largely for political rather than security reasons – the issue of the size of the various religious communities in Lebanon is so delicate that no-one wants to upset the political balance by actually counting the numbers in the different groups.

At least we have moved beyond this degree of sensitivity in Northern Ireland and it is widely accepted that a census of population is a valuable and important exercise.

The first results from the 2011 census for Northern Ireland released last week did not include analysis of the religion or ethnic background of the population – this will come later this year or early in 2013 – but it did include a mass of detail on the age distribution of the population and the structure of households.

There were not too many surprises in the first set of data that was released. The total population which breached 1.8 million for the first time had already been projected forward from the last census in 2001 to within 5,000 of the actual total by NISRA statisticians.

The net increase in the population over the 10 years since 2001 was 125,600, of which around 90,000 was natural growth in the population – births minus deaths.

The remaining 35,600 was accounted for by net inward migration, that is, the difference between the number of people moving into the region less the number leaving over the 10 years.

We already know that inward migration was much higher in the earlier part of the decade, following the expanded membership of the European Union. But it has fallen sharply during the prolonged economic downturn of the past few years, both with fewer inward migrants and more outward migrants as job opportunities in Northern Ireland have reduced.

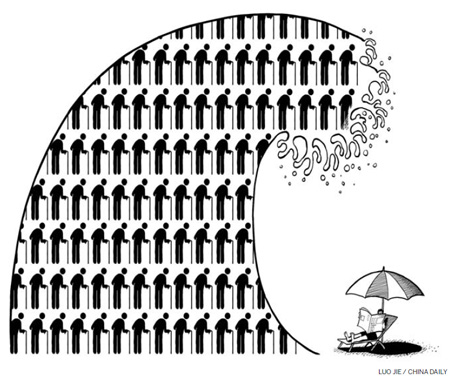

We also knew that the population was getting older and the census results confirm this. There are now 263,700 people aged 65 and over in Northern Ireland and 31,400 of these are aged 85 and over.

In percentage terms the proportion of elderly, at just below 15 per cent, is not as great as most other European countries – in Germany and Italy more than 20 per cent of the population is aged 65 or over and even in the UK as a whole the proportion of elderly has reached 16.4 per cent. By contrast the Republic has the lowest population of elderly of any European country at less than 12 per cent.

However, it is not just the proportion of elderly in the population that is of interest to policy makers but also the rate at which it is growing.

While Northern Ireland still has a relatively small population of elderly, it is rising at a much faster rate than rest of the UK. Between 2001 and 2011 the elderly population in Northern Ireland increased by more than 40,000 or 18 per cent, compared with an increase of just over 10 per cent in England and Wales.

In other words, we are getting older faster and this is already putting huge pressure on local health and social care services.

At the other end of the age profile we are at the top of the league table for the proportion of children in the population. Almost 20 per cent of the Northern Ireland population is aged under 15 and this is only exceeded in the rest of Europe by the Republic which has more than 21 per cent of the population in this age band.

In contrast with the elderly population, the proportion of young people is falling with obvious implications for policy-makers in the education and training sector.

One of the most interesting statistics to emerge from the census results was the growth in the population of pre-school age children in Northern Ireland which increased by 10 per cent over the past 10 years.

This minibulge in the population is attributed to recent increases in fertility and means that the school population will begin to rise again over the next few years.

What we don’t know yet is the geographical distribution of this pre-school age population and therefore which parts of Northern Ireland will experience this increased demand for schools. However, like the population of elderly it puts increasing pressure on scarce public resources.

Another public service provision pressure point highlighted by the census results is the growth in the number of households.

While the population grew by 7 per cent, the number of households in Northern Ireland rose by 12 per cent, as the number of people per household declined sharply. This was much faster than the rate of growth of households in other parts of the UK where it only reached 7.6 per cent. This clearly has implications for housing policy and for other household related services provided by central government and local authorities.

So is the huge cost of carrying out the census justified by the benefits we get from it?

This is going to be an ongoing debate over the next few years as we move towards the next census in 2021. The Lebanese may be able to manage without a census but public services in that country suffer the consequences of not having the information that allows them to plan. But so much information on the Northern Ireland population is now available on administrative databases that there is an argument for saying that if we could link all this together, then we wouldn’t need a census.

The idea of government even attempting this task would worry a lot of us. For the moment, I have a lot more faith in the 10-year Census.

Source: irishnews.com