Northern Ireland Dairy Firm Fears Brexit Impact on Border Trade

LONDON – With the outlook for the United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union still uncertain, dairy operators in Northern Ireland are in the dark about how their businesses will fare in a post-Brexit world.

With Prime Minister Boris Johnson committed to the United Kingdom’s withdrawal on Oct. 31 with or without an agreement with the bloc, one milk producer has warned it faces significant financial pain if Britain exits without a deal in place.

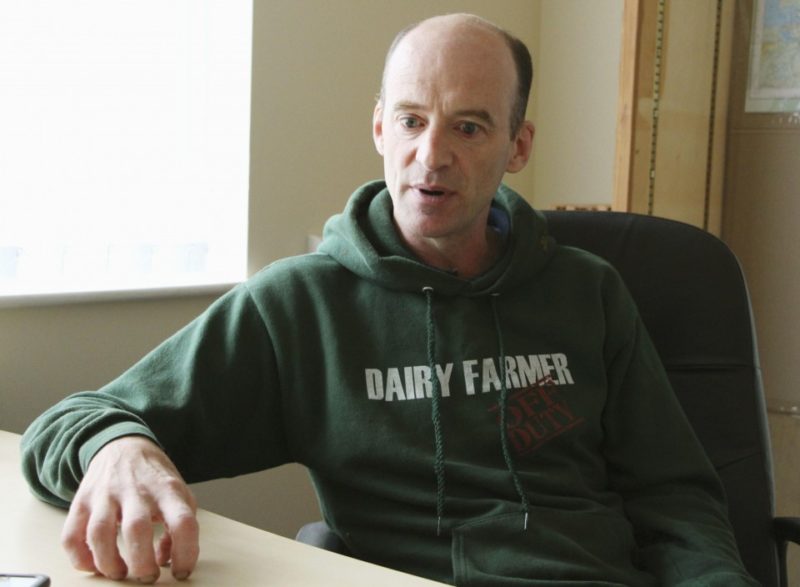

“The biggest problem for us would be a no-deal Brexit. We are clear that there are no benefits at all,” said 51-year old Cormac Cunningham, manager of Strathroy Dairy.

The firm transports milk from around 250 farms on both sides of the Irish border to its processing plant in Omagh, in Northern Ireland. After processing and bottling, the milk is distributed to supermarkets across Ireland, with over 60 percent of its output sold across the border.

Under current arrangements goods can be traded freely across the border between Northern Ireland, a part of the United Kingdom, and Ireland as both countries are members of the European Union.

“That has been brilliant for our business because we’ve been able to grow unhindered,” said Cunningham, whose father founded the company in 1980. The firm now processes around 220 million liters of milk every year.

After Brexit, however, these trading arrangements will almost certainly change.

Because the United Kingdom will no longer need to adhere to the European Union’s laws and regulations, products crossing the border from Northern Ireland to Ireland and vice versa may become subject to tariffs and checks.

“Potentially every single load of milk that leaves here to go south to Ireland will have to have a veterinary certificate,” said Cunningham, adding that controls on animal products tend to be much stricter than average due to the added health risks these goods can bring.

Cunningham fears what will happen if Strathroy Dairy is unable to meet any new regulatory requirements imposed after Brexit. “If we can’t send our milk to the south, then 60 percent of our business could be stopped overnight. That would make our company completely unviable,” he said.

Both the United Kingdom and the European Union have insisted they do not want to see any new customs infrastructure on the Irish border for fear of inflaming historical political tensions, but it is unclear how this could be avoided should goods checks be introduced.

A key part of Brexit negotiations so far has been the so-called backstop, a measure that aims to maintain a free and open Irish border.

The backstop aims to maintain peaceful north-south relations and facilitate a close relationship between the United Kingdom and the European bloc. It will apply if the two sides have not come to an agreement at the end of a transition period or if a deal does not guarantee a soft border, but will not apply under a no-deal scenario.

Cunningham said the lack of transparency over future trading arrangements has left businesses unable to plan, hampering growth. “We spent a lot of time talking to our suppliers to reassure them that we would do whatever we could to keep our business going,” he said. “But it’s made it much more difficult to get suppliers in the south to come to us.”

In the event of a no-deal Brexit, Cunningham expects there would be “uproar within the farming community,” with emergency measures implemented to avoid major disruption.

He urged the government to find a solution to allow businesses to continue trading.

“We have to accept the fact that whatever the outcome, if there is Brexit the flexibility we had to trade with Europe would be gone. That is a huge step back for us,” he said.

Source: kyodonews.net